Faces in the Trees

CW: Graphic Violence

Lucas was sitting in class in the mathematics building at Northern Kentucky University. He looked outside, through the splotchy smudge of the dirty classroom windows. He longed for the weekend. Lucas hated math class; he was only taking it because he was forced to – it was one of the unfortunate hurdles of completing his general-education requirements.

“Fucking general education,” Lucas thought to himself, “What a bunch of bovine excrement! Nobody goes to college for a general education, universities exist to produce experts in specific fields!”

Lucas was a bit pretentious. He wasn’t doing very well in math class – he was on track to get one of the only C’s of his college career – but it wasn’t because he didn’t understand the material. That’s what he told himself, at least. He could ace this stupid class, if he wanted to, he just couldn’t be bothered to give a shit about something like math. Even the math in this class. A ‘C’ was just fine with him. C’s get degrees, as so many of the students around campus loved to squawk by rote, like cockatoos.

Lucas was taking Math for Liberal Arts, the math class most arts, humanities, and social sciences majors enrolled in to fulfil the general education requirement for mathematics. The professor, Dr. Wyatt, asked some of the most pointless questions Lucas had ever heard:

“Imagine there’s a bus filled by an infinite number of people, and all of these people need to get rooms at a local hotel, which has an infinite number of rooms, but is also full; how can the passengers get rooms?”

What a stupid fucking question.

“They take the odd-numbered rooms!” Dr. Wyatt had yelled, “Since there are an infinite number of rooms in the hotel, you can give the current occupants all the even-numbered rooms and the bus passengers the odd rooms! It works!”

Those were the types of questions discussed every day in Math for Liberal Arts. Lucas couldn’t stand it. He was an art major. He liked sculpting and painting; that was his only passion – manipulating the raw, unemotional void of the world into a beautiful expression of his subjective vision. He had no time for infinitely large hotels and buses.

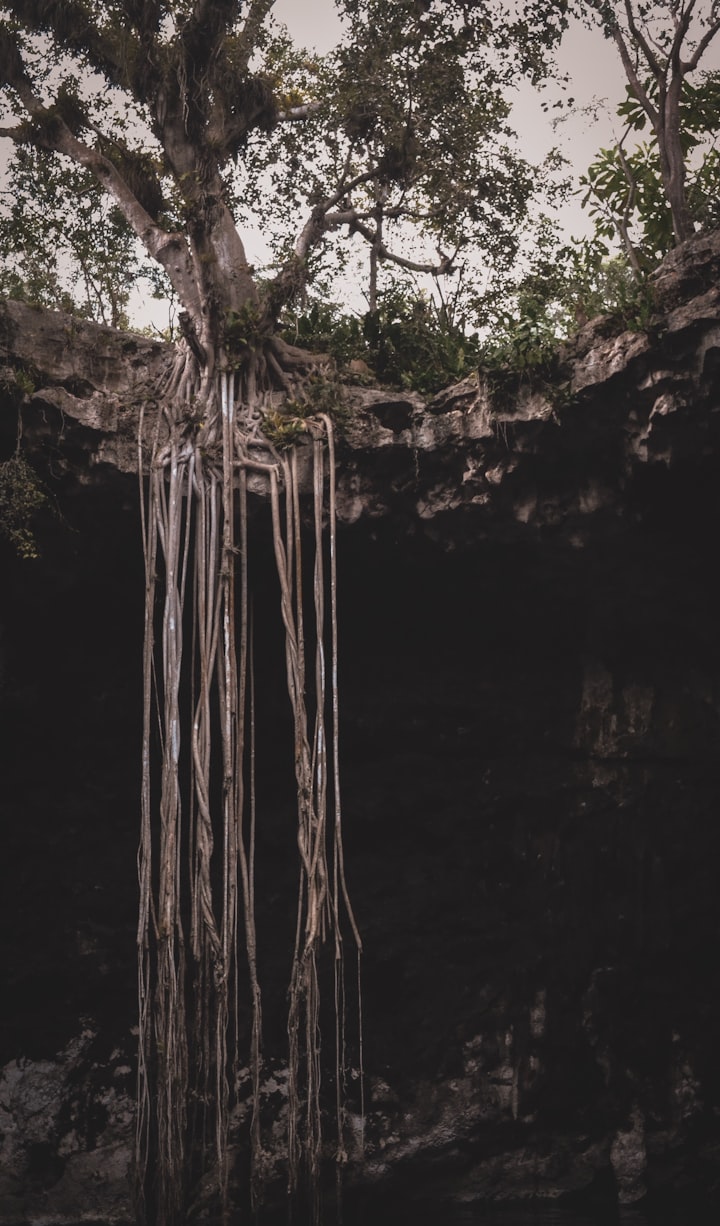

Lucas liked spending his time in the nearby wood. The art students were allowed to work out there, using it both as inspiration and as a living canvas. Lucas enjoyed spending time – far too much time, as his art professors had told him repeatedly – carving grouchy, startled, or apathetic faces into tree trunks. He liked taking walks through the woods at night, watching the encircling, shadowy floating expressions stare at him. They looked more real, at night, when he couldn’t see them so clearly. The mouths and eyes of their monotonous expressions appeared to be twisting simultaneously into wide-eyed grins and squinting grimaces. Lucas’s racing imagination further constructed their reality.

Dr. Wyatt strolled, nearly ten minutes late, excitedly into the classroom:

“Morning, my most excellent pupils!” he said, “Let’s continue our discussion about illusions, and the mathematics of the unreal.”

Lately, they had been discussing optical illusions, and how, just because something can be registered in your sensory experience, doesn’t mean your sensory experience isn’t lying. Sensory experience is created by the selection of evolutionarily beneficial traits, not by the truth of reality itself. They had looked at many examples in class. Dr. Wyatt connected these examples primarily to Lewis Carroll, whom he viewed as an obvious bridge between mathematicians and humanities majors. Lucas thought about his favorite album, Merriweather Post Pavilion, by Animal Collective; how its cover art rippled back and forth, as if moving. Optical illusions were at least artistically interesting, but they were mathematically useless. That’s what Lucas thought.

“Perception does not always equal reality!” shrieked Dr. Wyatt animatedly, his finger pointed to the ceiling in passionate declaration, his brittle, peppery beard quivering, his bald head shining, as if just waxed. “You may feel ten-feet tall! You may feel two-feet small! The world around you, at least as you experience it, may not even exist!”

In his excitement, Dr. Wyatt’s glasses fell from his face to the tile floor of the classroom. The lenses shattered with an innocent crack. He picked them up and reapplied them, laughing at himself wildly. His eyeballs, through the shattered lenses, looked to be sliced into several, size-shifting pieces.

“And alas!” he said, “I myself am forced to experience the unreliable, though natural perception of my own sensory experience. I can’t see shit!”

The class laughed, as if beginning to understand his point.

“Well,” he said, setting his broken glasses on the desk in front of the chalk board, “Like I said, just because you sense something – just because you see something – doesn’t mean that’s the way it really is. We are all reality-blind, to a large extent.”

Lucas’s interest was piqued, though he didn’t want to admit it.

“That’s what you will be considering for your class projects,” said Dr. Wyatt. “Think about optical illusions; think about patterns in nature. Why do they exist? Are they examples of reality in its true form, or some fabrication manufactured by our unreliable sensory experience? You will present your findings in class next week. That’s all… Have a good day!”

Dr. Wyatt paced briskly from the classroom, his loosely fit suspenders wavering in the breeze of his stride. He always showed up late, and he was always the first to leave. It was as if he had somewhere important to be. As if by habit, though, he reapplied his glasses before leaving the classroom, stopping stuttering in the doorway to feel with his trembling hands in front of himself. He traced the rectangular structure of the doorway before stepping cautiously through, momentarily brushing his hand across the surface of the fire alarm. He didn’t activate it, though.

Lucas took a walk through the woods on the way from class back to his dorm. He already knew the topic of his project; it took him no time at all to think it up. He would take photos of the faces in the trees – both during the daytime and at late at night – and compare the difference in appearance of the pairs of photos. He would also paint an example, showing the difference in the allegedly true reality of the photos and the subjective perception of the paintings. Lucas tried to maintain his peevishness about the class, but he couldn’t help but recognize his burgeoning excitement.

Flashing photos with his phone, he collected pictures of the faces in the trees – those faces he had previously, so meticulously, sculpted into the bark. One of the faces was an old man, with a beard much like Dr. Wyatt’s. Out from his mouth dangled a corn-cob pipe, smoke wafting liquidly up the ruffled bark of the tree. He was wearing a felt cap, shaped triangularly like the green one from the old Peter Pan Disney movie. Another face was a middle-aged, though ageing, woman. She had a severe look, as if something serious were on her mind. Lucas had wanted to emulate the woman in the American Gothic painting. A third was a child, and not just the face – this one a full-body sculpture. She stood gazing vacantly ahead, her eyes expressing endless depth – Lucas had drilled holes into the trunk of the tree – as a chaotic wildfire raged behind her. It looked as if to at any moment set the tree ablaze. Lucas had gotten quite good at carving in the trees, and these three pieces were his most cherished.

Lucas took plenty of pictures. He wanted the daytime photos to look true to form – he wanted them to appear sad. The photos at night, however, he would try and angle to seem happy, or at least content. That, he thought, reflected his true feelings – he preferred the night to the day. After collecting his photos, he would paint them. Maybe watercolor, perhaps oil – he hadn’t decided yet. He would make their appearance seem shifting, as if unpredictable – as if the genesis of a chaotic, dishonest reality.

Upon opening the door to his dorm, Lucas smelled the stench of his unfortunate temporary home. He was no clean freak, but his roommate, Keith, was much worse than him. Keith – who was a hairy individual – would shave, and then leave his hair scattered across the sink and bathroom floor. It was disgusting. Lucas told himself that he wouldn’t stoop to the level of cleaning up after Keith, but he couldn’t help it. Keith would never learn, and Lucas would much rather clean up after him and have a clean sink in which to brush and floss his teeth than risk inhaling the remnants of Keith’s ever-growing, prickly beard. Keith also never cleared his food from the refrigerator. Walking in the door, Lucas noticed something green – something fucking green – seeping out from the bottom of the fridge. Lucas couldn’t handle living in this dump – he needed a new roommate. That would have to wait until next semester, though; he could wait. Lucas considered himself a patient guy.

He uploaded the photos to his laptop and then printed them. He wasn’t going to get terribly fancy with this project – he was going to paste everything creatively on a large poster-board and then color in its background some chaotic, swirling unreality.

Twisting open his glue stick, he pasted the first set of pictures – the afternoon photos – onto the poster board. He then got to work on painting his own alleged, psychologically subjective, sensory perception of the daytime images. He decided to use watercolor for the afternoon images, and oil for the nighttime ones.

Everything came out perfectly – just as Lucas had wanted. Pasting the last of the three afternoon paintings – all of which he had constructed in only a couple of hours – he stepped back to gaze proudly at his work, in his backstep accidentally kicking some remnant trash – a plastic, empty Taco Bell quesadilla bag – and smiled big. The old man looked true to form. The smoke from his pipe billowed in a rainbow of color upward out of the canvas of the printer paper. Lucas had colored it further with crayons, up and off the poster board. The pensive woman glared ahead, some darkness somehow glistening from her eyes. The little girl stood at the bottom of the poster, the fire behind her raging as if to ignite the thick paper. Lucas was satisfied.

“Now I just have to wait until around three in the morning,” he thought, “It will be as dark as it can possibly get, then. The woods will be perfect.”

Lucas lay in his bed, snoozing only briefly before hearing the door open with clicking irritation.

“Hey, man!” said Keith. He strolled happily into the room. He always seemed so clueless, Lucas thought.

“What are you getting into, tonight? It’s the weekend! Let’s do something!”

As much as Lucas told himself he disliked Keith, he did hang out with him often. Lucas didn’t have many friends, and the two of them enjoyed getting a dub-sack and a case of PBR and playing old video games late into the night. Recently, they had been cruising through Majora’s Mask on Lucas’s old N64 – one of the transparent, lime green models – he had brought from his hometown to college.

“I can’t, tonight,” said Lucas, “I’ve got a school project to work on.”

“School project?” said Keith, “It’s fucking Friday! The weekend! We don’t do school shit on the weekend.”

“Maybe you don’t, but sometimes I have to. I’m fucking up this stupid math class; I might wind up getting a C.”

“You know how many C’s I’ve gotten?” said Keith, “A shit-ton! C’s get degrees, my brother.”

“I know,” said Lucas, “But I’d rather get better grades than that. This class is pissing me off. The professor, Dr. Wyatt – he’s crazier than shit. I can’t stand him. I want to create something good to show him what’s what. Something he has to give an ‘A’.”

“Suit yourself,” said Keith, “I guess that means no Majora’s Mask tonight, huh?”

“No Majoa’s Mask tonight.”

“Whatever. I guess I’ll just blast some bastards online, on Halo 3.”

“That sounds like a good idea,” concluded Lucas.

Lucas would have loved to play Halo 3 all night, too, but he was determined. He was going to the forest, and he was going to do it with a full tank of energy, at 3am.

After flailing around in bed for a while, listening to the sound of Keith getting stoned – smoking from a bong manufactured from some aluminum foil and a two-liter bottle of Coke – and hearing the rattle of the battle-rifle gunshots on Halo, Lucas finally dozed off.

Keith was snoring in his gaming chair when Lucas awoke. His bong, nestled next to his chair in front of the blank, orb-like light of the TV, was still smoldering. Lucas picked up the plastic bottle and took a couple healthy rips before dousing and trashing it. It might be good, he thought; it would alter his state of mind before venturing into the woods.

The R.A. on duty was snoozing at the reception desk as Lucas made his way out of the building. Campus was mostly black other than scattered streetlamps illuminating narrow roads and walking paths like giant, guardian fireflies. Never completely quiet on the weekend, Lucas heard distant, shouting voices from some of the adjacent dormitories – both excited and angry yells.

He scampered toward the wood quickly, darting through the parking lot stealthily like he did through the Southern Swamp in Majora’s Mask; like he did through Last Resort in Halo 3. The bud was kicking in. He saw and felt a glowing, cartoonish warmth emanating from each physical object – mostly cars – as he scurried passed. Glancing into the side-view mirror of a car, Lucas saw himself. He gave a surprised, wide-eyed grimace before laughing aloud. Before entering the wood, he saw scampering within the trees a trio of raccoons. They were fat, waddling happily into the dense foliage. One of them carried a stolen, yellow bag of Lay’s potato chips. The students, and the school’s dumpsters, kept them well-fed.

The forest was black as pitch. Lucas could use the flashlight on his phone – he knew that – but he knew this forest; he could feel it. He needed the darkness; it was beneficial to his art. He wanted to make it to his favorite, most prized group of trees by touch alone, seeing on his journey the dark, watchful shade of his other, unchosen sculptures.

He stepped through the wood to his first subject – the old man with the smoking pipe – relatively easily. He gazed into the man’s eyes, in his stoned state moving his face only an inch from the thoughtful man’s.

“I’ve come back for you,” said Lucas, giggling.

“And I’ve come for you!” said the tree.

Lucas fell back to the soft forest floor.

It wasn’t the tree, though. Lucas blinked. Turning, he looked behind. Dr. Wyatt stood shadowy within the trees, leaning on the face of the sculpture of the pensive woman; the only light from him emanating outward from the static of his electric, lengthy white beard.

“You didn’t think only the art students knew about this place, did you?” he continued. “This is my favorite place on campus, as well. I can’t always enjoy it, though – unfortunately. I must watch from the shelter of the brush, batting away mosquitos while you kids desecrate the trees.”

“What?” said Lucas.

Dr. Wyatt took a step forward, his neck twitchy as if by uncontrollable reflex. His eyes widened; they were blood-red – even redder than Lucas’s, who was by this point blazed off his ass.

“You artists…” said Dr. Wyatt, “I’m a mathematician! I deal in the objective, in the inarguable nature of reality itself – reality that transcends the subjective unreliability of our sensory experience, experience bound so tragically to the absurd trudge of human evolution.”

“But…” said Lucas, “You said that reality is subjective, that just because we see something, doesn’t mean it’s actually there.”

“I said no such nonsense! I said that our experience with reality is unreliable. And it’s true! It’s so unfortunately true… But we who study math – the most objective of all the sciences – we are the ones who deal so bravely with reality as it is truly composed. No other science – not even physics, not even chemistry – can feel truly confident about the findings of its research. It’s all based on us – the human animal! And what a tricky, deceptive animal we are. Evolution has itself shaped us to exist in a fairy tale; a fictional world the safety of which shelters us from the brutal truth of the unemotional void of reality. Math rejects that safety. Numbers are reality, just as Pythagoras discovered thousands of years ago. But no! No one listened to him; those romantic Greeks were all smitten with the unreality of Plato’s rambling, romantic fiction. His ludicrous literary cave. You can’t use so-called art to explain reality, and you can’t trust reality to uncover itself. Self-expression is a blockade to the truth. It is the responsibility of we mathematicians to fix this ancient social issue. It is the meaning of our existence.”

Dr. Wyatt took another step toward Lucas, opening his ragged, brown suit-jacket, reaching in the strangely deep pocket and flipping open a red pruning saw.

“I hate destroying trees,” he continued, “They’re so geometrical – so perfect. Pythagoras loved trees, I’m sure. But this tree is no longer perfect; you have desecrated its universal logic with your absurd art.”

Scurrying backward, crab-like away from Dr. Wyatt, toward the base of the tree, Lucas stopped, sitting in the chalky dirt, panting heavily beneath the sculpture of the pipe-smoking elderly man.

“But you’re the math for liberal arts professor!” said Lucas.

“And I’ve always despised that class!” said Dr. Wyatt, “It’s like teaching pre-school. There’s nothing interesting or challenging about it. I only do it in hopes that one of you disgusting lot will see the error in your ways and decided to devote yourself to something worthwhile. Something simple, perhaps. Something organized; part of a system – something that will benefit the research of the mathematicians. Now get out the way, I need to destroy these sculptures.”

Lucas, his confidence temporarily renewed, stood, spreading his arms protectively to shield the tree.

“You’re not going to destroy my art,” he said.

“If you don’t move, said Dr. Wyatt, I’ll have to remove you forcibly.”

Lucas didn’t move.

“Fine by me,” said Dr. Wyatt. He raised his pruning saw, a manic giggle escaping his sweaty, quivering lips. He paced toward Lucas, who – realizing he had no weapon of his own – shielded himself from the blow of the saw.

“Hey!” came an abrupt voice from behind.

Dr. Wyatt, frustrated though still in a frenzy, turned. It was Keith, standing at the edge of the clearing.

“Hey!” came another call.

“You already said that, you dumb bastard,” said Dr. Wyatt, “What, are you another art student? That would make a lot of sense. Fucking idiots.”

“Uh, I didn’t say anything,” said Keith, “Hey! Aren’t you Dr. Wyatt? What are you doing out here so late? You know, Lucas really wants to make a good project for your class. He skipped weekend Zelda and Halo for it! I had to play by myself!”

Dr. Wyatt stood momentarily confused, as if in consideration – his light khaki Sperry’s shuffling in the dry dirt of the forest floor. Finally, jiggling the saw in his hand like a teacher’s whiteboard marker, he took a confident, pacing step toward Keith.

“The fuck?” said Keith.

“You shouldn’t have come here,” said Dr. Wyatt, raising his saw.

He slung it down hard onto Keith’s gangly neck, the target of which was near impossible to miss. Keith gave a muffled squawk, like a startled ostrich, before falling silently to the dirt. Dr. Wyatt swung down upon him again and again. Keith’s thick blood pooled with the chalky dirt, the creation of which looked the product of a morbid bakery. Blood covered Dr. Wyatt’s jacket, beard, and still-cracked glasses.

Keith never had a chance.

Dr. Wyatt looked down upon Keith’s body only briefly before turning back to Lucas.

“Now you know I’m not kidding,” he said. “You’d better get out of the way of that tree.”

Lucas, with no idea of what he should do, braced himself for the impact of Dr. Wyatt’s reddened saw.

“Hey!” came a voice from behind.

Dr. Wyatt grunted in annoyance: “How many people do you hang out with in the forest?” he said.

He turned. There was no one there.

“Hey!” came another voice. Dr. Wyatt, staring in the direction of the empty call, took a step back.

Out from within the blackness of the woods emerged a woman. Middle-aged, she looked pensive. She glared at Dr. Watt as if sizing him up. From the other side of the edge of the clearing entered another figure: a little girl. She stared into Dr. Wyatt’s quivering, chaotically blinking eyes. Her body was aflame; her hair crackling ablaze – ethereal smoke wafted up from her head into the forest canopy.

“Who are you?” said Dr. Wyatt.

“Hey,” came a voice from behind.

Dr. Wyatt turned.

An elderly man now stood by the tree, near Lucas. His face appeared tried, though his eyes were shielded by a loosely hanging, triangular green cap. Smoke from his corn-cob pipe wafted fusing with that of the little girl’s flaming head.

“Art is real,” they said in monotonous unison, moving toward Dr. Wyatt, who had stumbled to the dirt.

“What is this?” he said, “This doesn’t make sense! This isn’t order! I must be dreaming! It… it must be my anxiety… I must be having another episode…”

They continued their ghostly trudge. “Art is real,” they continued.

Their spectral figures fusing forcibly into Dr. Wyatt, they set his body aflame. Shrieking, he ran flailing around the forest clearing before falling into the dry dirt, the blaze eventually muffled with no remaining fuel for its fire.

Lucas stood bewildered. He looked at the life he had breathed artistically into these seemingly living beings. They stared at him in unison before nodding and disappearing into the trees. Their presence gone, Lucas noticed Keith’s lifeless body at the edge of the forest clearing. He rushed to his unappreciated friend, kneeling beside him.

Keith was dead. Lucas wept, heaving dust and remnant smoke from the otherworldly fires into his lungs.

Placing his head onto Keith’s bloodstained chest, Lucas continued crying. His tears merged with the blood on Keith’s shirt – a random tie-dye from Wal-Mart – to create an abstract, though strangely human work of art.

Lucas looked up to the trees – his creations.

“Art is reality,” they seemed to say through the wind of their creaking branches.

Lucas blinked. He cried again.

Above the trees, the brightness of a new morning was emerging.

Robert Pettus is an English as a Second Language teacher at the University of Cincinnati. Previously, he taught for four years in a combination of rural Thailand and Moscow, Russia. He was most recently accepted for publication at Allegory Magazine, The Horror Tree, White Cat Publications, Savage Planet, Short-Story.me, Kaidankai, Tall Tale TV, The Corner Bar, A Thin Line of Anxiety, Schlock!, Black Petals, Inscape Literary Journal of Morehead State University, Yellow Mama, Apocalypse-Confidential, Mystery Tribune, Blood Moon Rising, and The Green Shoes Sanctuary. "Faces in the Trees" is one of the stories he recently wrote.