A Hand In The Clouds

Arthur worked this job. It was a job that he didn’t understand. It was a job that nobody understood. It was a job that required him to drive to these towns and villages and neighborhoods and look at the trees.

By Max Newman

Arthur looked at the stars and thought that if he could reach high enough he could pluck them out of the sky and eat them.

“I think that if I reached high enough, I could pluck them out of the sky and eat them,” he told Suzanne.

“What the fuck are you talking about,” replied Suzanne, she who knew night from day, she who could hold an apple blindfolded and tell you which type of apple it was. Arthur was disappointed at this response, but was not shocked; it was words like this that he realized Suzanne wanted him to say less of. So he closed his mouth and sat and looked at the stars and continued to think about how if he could reach high enough he could pluck them out of the sky and eat them.

They were perched on two boulders in a field, two pockmarks on a sea of green. Neither actually remembered how they had arrived in the field in the first place. It was one of those nights where the moon never fully permeated the thick blanket of clouds that danced around it, never fully bursting through to shout, “I’m the moon! Look at me! I am so luminous and gargantuan and perfect!”

Their heads glued to the sky, minutes passed before another word was spoken, outside of the unspoken ones that drifted up from their heads into the night and into the invisible sun and into the stars and everything beyond. Suzanne was the one to break the silence.

“It’s crazy to me that there are people that can’t witness this. It’s actually pretty horrifying.”

Arthur pondered this for a second. It was something he didn’t often think about. He was realizing he didn’t think about a lot of things as much as he would want to. “Yeah. Damn. If I was in a city or something like… yeah. Shit.” Arthur didn’t have much to add to Suzanne’s statement, such was its encompassing horror.

“No. Like, I’m talking about the sky Arthur. The whole sky. Like under the Cooling Dome.”

Arthur was confused by this statement. He leaned forward upon his rocky throne pensively. “Wait, but like, you can still see through the Cooling Dome, right? I mean it’s not made of steel or wood or anything.”

“It’s not like that. Like yeah, when I lived under it I could obviously still see SOMETHING, but it’s not the same. Whatever material Exxon made it out of creates these weird refractions. It’s like looking at the sky through a glass of water. Actually, no. Like through some type of weird stained glass. I don’t know. It’s not very pretty to look at.” Suzanne had a look on her face as if she was thinking about the act of consuming a lemon.

Arthur was despondent. How had he never thought about this? How had he not remembered those who cannot look into the sky and wonder if the moon is looking back, bright and bold, if the comets will pepper space rocks upon the willows and oaks and the grass, if the sky will fully collapse and fall and eat all of those beneath it’s blanket-esque grasp? Sometimes Arthur wondered how he noticed anything at all.

“But, I mean, I feel like it’s a tradeoff. Like there’s not seeing the stars, but then there’s, like, melting alive.”

Suzanne slowly turned her head towards Arthur, like a barge in the harbor. “You know, I think… Arthur, I think sometimes…” She stared past him for a moment, sighed, and turned her head back, slow as molasses.

Sometimes Arthur wished that people would finish their thoughts. Arthur wanted to know what was going on around him, why his toes brushed the dirt that lined the rock he was sitting on, why his eyes hurt in the sun, what the birds and ants were saying to one another. He wished he knew where to start.

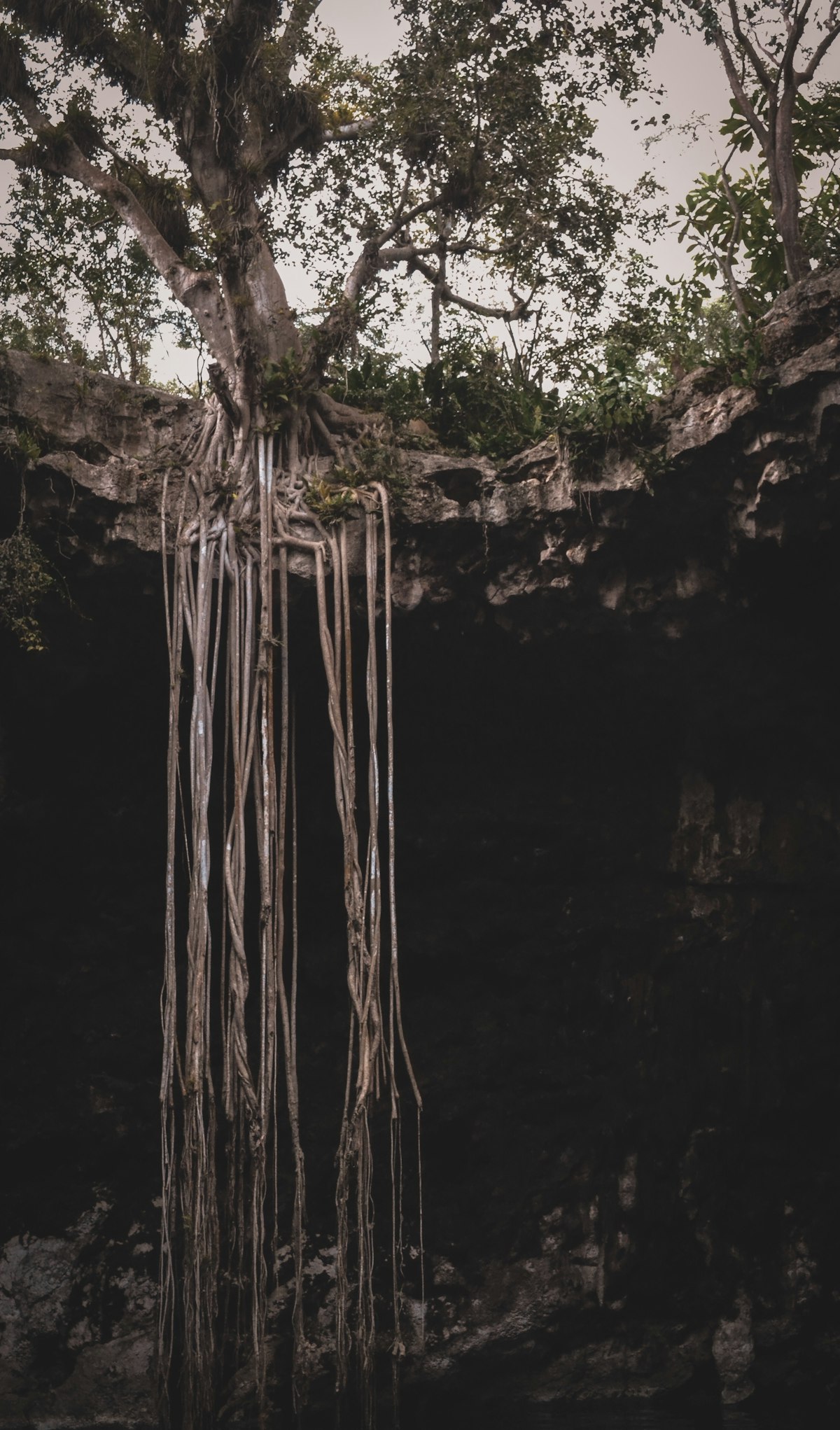

Arthur worked this job. It was a job that he didn’t understand. It was a job that nobody understood. It was a job that required him to drive to these towns and villages and neighborhoods and look at the trees. He had been given the car three years previously, when he had inherited the job from his friend Michael. “They're letting me look at shrubs now,” Michael had joked, as he slipped the rusted keys into Arthur’s apathetic hands. Michael had never actually said why he was leaving the job. He may have been fired. Arthur hated the car, and thought that it smelled like the inside of a tumor. He was grateful to have the job, but he didn’t really know what he was doing. He would get these certificates of excellence from the government. They talked of the “honorable service” that Arthur was providing. Whenever he told his parents about his job, they would always tell him what a wonderful thing he was doing. Arthur didn’t feel as though he was actually doing anything special at all, but he liked looking at the trees. He cycled through the towns on this shit-stained list in the car’s glove compartment, and just ambled around, shoes slapping pavement and kissing grass and toeing rocks, eyes on fine cherry bark and the elegant beeches and the flaky maples. Arthur found himself especially mesmerized by the imperfections of the tree branches, how no single one was the same, each one spidering off on its own path and clutching leaves and acorns and berries. When the wind would drift in, and the leaves and branches would sway and wave and dip and weave, Arthur liked to wave back. He thought himself to be friends with the trees. Sometimes, birds and squirrels would make brief appearances, before darting back into their homes in a state of unconcealed panic. Arthur hated that they were scared of him. Once, a squirrel had wandered out onto a branch above Arthur’s head, just strutted out there one foot after another, like it owned the place, like a god, and threw an acorn full force at Arthur’s head. The acorn thunked against the side of Arthur’s skull like a tiny, painful dodgeball. It made Arthur feel alive. It was the most alive he had felt in a while.

Arthur had known Suzanne for about three years now. Suzanne and her father moved up north after fleeing Louisiana for “political reasons.” Arthur didn’t know all of the details, but he had gathered that it had something to do with her father’s refusal to pay the gratitude tax for his residency in the region beneath Exxon’s Southern Cooling Dome. He was now living under the assumed name Jensen, and never left his house. On the few occasions that Suzanne had let Arthur visit her isolated, beige-souled, spectral home, Jensen was perched atop a wooden stool, looking out a cracked screen door in the house’s small kitchen. It seemed as though he was not looking at or through the window, but rather through everything. There was this one, stately tree in the backyard that his eyes sometimes seemed to drift towards. The way he looked at it made Arthur feel like if he ran full force at its trunk, he would drift right through to the other side. Jensen was certainly not a talker. Often, Arthur would try to greet him, and would be met by some sort of unfriendly and incoherent murmur. Some of Arthur’s favorites were “mmmh”, “grrrrm”, and “aaeh”. Arthur wondered what was going on behind those hollowed out eyes, crown of lint metal tooth glue colored hair like a halo around the glint of a bald spot, and the despairing and curved back. Once, he had overheard Arthur talking about his job, and laughed so hard that he fell off the stool, writhing around on the floor, guffawing and cackling with delirium against the linoleum. After about a minute, he collected himself, and re-perched himself atop his faithful stool, just as empty and limp as before. Arthur had never before seen him display anything close to that capacity for feeling, and would never see it ever again.

Suzanne loved Arthur, and also wanted nothing more than for him to feel what she felt. “I want to be able to talk to the rabbits,” he would murmur, one corner of his lip turned jauntily upwards as was his trademark smile. “Imagine how cool that would be.” Even in his frequent spells of sadness and emptiness that he confided in her about, he had this childlike wonder about everything around him. Suzanne appreciated this. In fact, she was quite envious of him; He could bring her happiness in the blink of an eye like not even she herself could. A day of eroding by herself in bed could be turned by a visit from Arthur into a mad dash to purchase ice cream, to buy a new pair of socks, to jump fully clothed into a river and swim and swim and frolic and swim. These were the times that were beautiful. However, what really pissed her off to no end was his blindness, the things he could not see. He couldn’t find the solution to any sort of deep-seated problem unless it walked up to him and slapped him in the face. He could see and recognize sadness, anger, despair. But everything was taken at face value. He dealt with his own depression by turning every which way apart from inwards. At no point was there a thought of self reflection. “Maybe I need to take up yoga,” he would tell Suzanne. “I definitely need to be eating more oranges.” He was a treelooker, for God’s sake. He vehemently refused any suggestions that he could be indirectly payrolled by Exxon. Why would an oil company care about trees? He was so close. He thought all the things around him were so beautiful. Some interesting rock on the side of the road, a delicious bowl of soup. The ergonomics of a seatbelt, the smell of a fresh piece of printer paper. But he was one to leave a snowball in the open air, trust the sun, and get sad when it melted; one to cook the perfect steak in the eyesight of a bear, walk away, and then come back and wonder where the glistening slab of meat had run off to. He trusted too much. He thought too little. He probably thought he could fix the world with fucking Scotch tape.

Arthur loved Suzanne, and also wanted nothing more for her to feel what he felt. She had this practicality about things that Arthur just could not find in himself. It was a stabilizing presence. She was direct, and she knew exactly just what she wanted, and when she gazed at something or smelled something or heard something she gazed and smelled and heard with intent. “You’re an idiot”, she would often tell him in the midst of one of his tangents, in the midst of a daydream, as she narrowed her eyes, irises so dark they formed a giant midnight orb with her pupils. And sometimes, this was exactly what he needed; in his world of gray areas, in his job, in himself, he appreciated this. In fact, he was quite envious of her. She could bring him happiness in the blink of an eye like not even he himself could. A day of eroding by himself in bed could be turned by a visit from Suzanne into a journey to prance through a tree-lined field, to find the perfect cup of coffee, to find themselves in a suburban cul-de-sac under the cool blanket of moonlight and dance and dance and cackle and feel. These were the times that were beautiful. But what really pissed him off to no end was her cynicism, her inability to live in the moment. She got mad when he pointed this out, incensed that he couldn’t see beyond the beauty around him. “You’re not fucking DOING anything”, she would say. “Time is moving so fast, Arthur.” But if time moved so fast, what was wrong with appreciating the pattern of a rug, the sound of the feet on wet grass, the screech of car tires on a paved road? Why not do it while it’s possible? He didn’t know how to help. He didn’t know how to help himself. He didn’t know how to help the trees. He didn’t know how to help the sun. All he could do was trust. Suzanne told him that he trusted too much, he thought too little. But Arthur knew of nothing else to do with himself. He was a fish in a million miles of open ocean, a baby bird in an unending sky, sky of closed books and doors with no handles. So he trusted. He trusted and trusted and would trust until the trust was blown into a million little pieces and he could trust no more.

Arthur was beginning to feel the change of the seasons, the air beginning to turn, the sickly sweet watermelon sunrise sweat grassdew Summer beginning to morph into Autumn. But he also felt the air beginning to turn in other ways. He was looking at this tree. It was an absolutely ancient oak tree, with a trunk that was as thick as a small car. He had ventured into this suburb, one of those plasticine angular robot lawn suburbs with trees that could be counted on two hands. This tree was an anomaly, monolithic in an alien-esque way as it hung over row after row of cookie cutter houses almost as if it was going, “fuck you, I’m gonna stain this pristine little fucking town with my green and my squirrels and my sap and my fungi and my everything.” There was this house directly next to the tree that was so unblemished that it almost looked as if it had been molded from rubber, as if it was lived in by automatons. Arthur thought it looked like an exhibit in a museum. He stood so that both the tree and house were equal parts in his eyesight. He thought that the contrast between the house and the aggressive imperfection of the tree was one of the most incredible things. Under the shadow of the thick foliage above his head, he thought about how easy his life would be if everything was this clearly defined, if everything was this obvious.

“Too bad it’s not,” said the tree.

Arthur, who’s eyes had glazed over as he stood deep in thought, took a second to snap out of this stupor. He was surprised by his own lack of surprise at this development. He had been surprised at his own lack of surprise for as long as he could remember. He stopped for a minute, took a purposeful step in the direction of the thick oak bark, and declared to no one in particular: “I think that tree just talked.” He wasn’t wrong. There was some sort of voice emanating from somewhere within the dense trunk. It was not a confident voice, but rather seemed like a burnt tissue, frail and cracking. Arthur always imagined trees sounding more confident than this. He imagined a tree’s voice like steel, like a bodybuilder’s bicep. But this was a tattered murmur, a melted icicle. Eyes fixed on the tree’s grooves and sap, Arthur began to listen to the soft words that followed the rather negative declaration.

“Psssstssmbompbmmm… bzhmmm… tfrrrrst…”

At first it sounded like gibberish, but, continuing to step closer to the rich bark, so close that he could smell its ancient coffee crunchy nutty aroma, Arthur began to make out some fleeting words.

“Nasdaq… NYSE…”

Arthur pressed his ear to the tree, scraping his ear against this body with hidden vocal chords, straining to make sure he was hearing clearly.

“Nat Gas plus zero point zero zero zero eight… silver minus zero point zero five nine…” The tree, this natural bastion of something that Arthur couldn’t understand but revered, the pillar amongst the ruins, was reciting stocks. In that voice that could have been broken with the bare hands, teetering and unsure, numbers and acronyms and abbreviations were being rattled off as if being read off a screen, as if the tree itself had been planted and grown and nurtured for this very purpose.

“VIX minus zero point thirty-four… UTIL minus three point zero nine…” As he slowly slumped down the tree until his bottom rested upon its spidery maze of roots, ear still pasted to its trunk, Arthur began to feel an emotion that he knew he had felt many times previously, but could not quite identify. Arthur knew that he was not the best at self analysis, but for a moment he dug deep, he stretched old muscles and turned around in himself and searched and searched for what it was, what that feeling was.

“Wheat minus one point five… corn minus one point twenty-five…”

A lime-colored leaf, aggressively flawless in its shape, shaped like it had just come out of an encyclopedia dedicated specifically to leaves, shaped like it knew its own perfection, drifted down the length of the talking tree and planted itself on Arthur’s shoulder.

“NASD one hundred plus six point eighty-five… copper minus zero point zero zero zero one…”

And Arthur caught the feeling. It was the feeling of being thrown like a ragdoll, like a limp piece of pasta over a waterfall, having a wound tended to by a shark, being launched in a rocket bullet cannonball deathly indescribable fashion directly into the sun. It was the feeling that Arthur had felt had lingered over his own head for longer than he could remember, like a skyscraper with weapons. It was that feeling of helplessness. It was paralysis, it was defenselessness. And Arthur let the feeling wash over him, a gust of wind over a field, a perfect chord that tickles the ears, a perfect wave that eats and destroys. Arthur realized that he really didn’t know much about anything at all.

“RBOB Gas plus zero point zero one one… soybean minus three point twenty-five…”

And he wanted to so badly. He wanted it more than anything. But in the end, he was nothing more than a blind canary in a mine, a legless grasshopper. He was destined to know of nothing.

Arthur thought he could invent a new type of soup.

"I think we should invent a new type of soup. Something with radishes.”

“What the fuck are you talking about,” replied Suzanne, she who knew her favorite shade of gray, she who could find a needle in a haystack with only her mind.

Arthur was disappointed at this response, but was not shocked; it was words like this that he realized Suzanne wanted him to say less of. So he closed his mouth and sat and looked at the stars and continued to think about how he could invent a new type of soup.

They were perched on two boulders in a field once again, once again those two pockmarks on a sea of green. Neither actually remembered how they had arrived in the field in the first place. It was another night where the moon never fully permeated the thick blanket of clouds that danced around it, never fully bursting through to shout, “I’m the moon! Look at me! I am so vibrant and enormous and wonderful!”

Their heads glued to the sky, minutes passed before another word was spoken, outside of the unspoken ones that drifted up from their heads into the night and into asteroids and into the planets and everything beyond. Suzanne was the one to break the silence.

“Do you remember when I was talking about not being able to see the sky?” Arthur turned and looked into Suzanne’s cavernous eyes. “Yeah. I wanted to tell you something about that.”

“You wanted to tell me something about that?”

“Yeah.” Arthur wearily rubbed his left temple. “I think I realized something.”

Suzanne leaned back, relaxed as a stretched muscle.

Arthur looked upwards. “If Exxon made the Cooling Dome, doesn’t that mean they make the sky?”

Suzanne stopped for a moment, still as the rock she sat atop. “What exactly do you mean?”

“Like, at the end of the day, at this point, the cooling dome is the climate, and we are the sky. And I worry that we’re in too deep, like, there’s nothing we can do about it.” Arthur fixed his eyes on a point in the landscape of the night and squinted as if he were reading a book. “It’s like an invisible rope that’s tying me to the rabbits and the stones and all of those things, but it’s too tight for me to untie.”

And Suzanne thought for a moment, thought about Arthur’s statement that seemed so inconsequential yet felt the size of galaxies. On the one hand, she was happy for this unprecedented self-reflection that Arthur seemed to be engaging in. But it also took her aback somewhat. So she paused and she thought. She thought in the nocturnal opacity of the field, in a sea of crickets and in a sea that was in her head and under the lights that were there and not there and above the ground that extended below her feet in a tight and compact parade of dirt. And she thought about her father and her house and her life and where she had come from and where she was and where she would never be. And she realized Arthur was right.

“I don’t like it,” said Arthur, peering into his shoelaces.

And they both looked up again, and there they both were. They saw themselves in the stars and against the blackness of night. Pasted against the sky, like they owned the place. And maybe they did.

It was either a Tuesday or a Wednesday when it happened. Arthur was not quite sure at the time. He had woken up with an inkling, had a premonition that the shifting he had been perceiving was all too real, that something drastic and important and undeniable was about to occur. He was not quite sure exactly what, but he knew that he was right, knew he was right with the confidence that he knew his own name. And it was on that particular Tuesday-Wednesday that Arthur pulled into a town from his ragged broken yellowed list in his ragged broken yellowed car and saw it.

The people were coming out of the trees. He had been here a few times before, but this was the first time that the rugged bark had attached itself with an iron grip to the arms and the legs and backs of the weary inhabitants of this invisible village. There were people with roots tangled around their forearms, planted spread-eagled against ground as if in handcuffs. There were people on their stomachs, trees growing from their backs, pinning down their hosts like a defiantly victorious wrestler, climbing into the blue white elephant hyacinth ocean rubber sky until they tickled the moon. There were people with hair of mushrooms and fingernails of wood and legs that became branches that became twigs that daintily caressed berries and acorns and buds. There were people with eyes of rock staring at their hands on which fingers had disappeared and had been replaced by flowers of every kind, orchid thumbs and rose ring fingers and carnation pinkies and fingers of sunflower seed. They were flowers and they were trees and they were the sky and they were the dirt and the animals. They were the world.

Arthur got out of his car, parked on a street of rotting pavement, and just stood there, just stood there and thought and thought and held a chest full of neither confusion nor shock. And as he stood there against the weight of the sun and the weight of the ground as they both closed in on him, he began to realize something, began to look a little closer. This parasitic fauna was no bastion of natural beauty. The rugged bark was not so rugged, but rather tattered and frail like old parchment paper, faded through time and separating from its wooden home. The roots were dry and spidery and looked as if they had been hit with a storm of sandpaper, looked as if they were ready to wither and erode away and disappear within themselves. The trees were not confident, but tentative and apprehensive, ready to fall, touching the sky not in a victorious act but in an act of desperation, desperate to escape, desperate to rip through the atmosphere and free themselves and free everyone. The acorns and berries and buds were all dead and cracked and withered and all the nutrients and value they had provided was gone now, gone to time, gone to a corner of reality that was locked away like a million dollar safe, forever. And the flowers, oh those flowers. Petals dancing in the wind as they fell from aching stems, dances of death, dancing onto a ground that was uninviting and screamed for something that it would never get.

And Arthur noticed this, and as he noticed this he looked down at his oblivious shoes, and as he looked down at the leather and the laces and the stitching he began to see the wispy beginnings of weeds meshing themselves onto his own feet. And Arthur couldn’t help but think that this was the culmination of something, that this was the culmination of an inevitable force colliding with the world that Arthur was so often befuddled by.

And he didn’t like it. Arthur didn’t like that he was so tied to this thing that he did not understand, that everyone around him either didn’t understand or wasn’t willing to explain. A problem in which everyone who could do anything to help wouldn’t do anything to help. And Arthur was mad and he was furious and he was despairing and he was bewildered and he was everything that he wanted not to be. And he leaned down to his toes, toes of limp and corroding yet fixed roots, and he talked. He talked to the roots.

“Hey.” His voice wavered slightly. “Could you please stop attaching yourself to me?” And Arthur knew he would get a response, and when he did it was from a voice like popped bubbles.

“I don’t know how.”

And Arthur looked down at the growth that he told himself in vain was not truly a part of him, and he sighed, sighed in resignation, sighed for what felt like years, and he spoke. “Me neither.”

And he collapsed onto his rear end, and he sat there, sat there hugging his knees close to his chest. And he realized that he was the confident squawk of a chicken. He was the gradual pinpointing of a branch into a twig. He was a blemish that was a cloud in an otherwise blue sky. He was a shrimp in the ocean that sat belligerently, guarding a coral orifice. He was a footprint of a hooved animal that ate into dirt. But he was also the sputter of coffee into a cup for weary eyes. He was the burning crunch of fingers on a keyboard. He was the taste of candy and the view from an office building out onto a city, a metropolis that extended forever. And he sat there, he sat there like everything, like nothing, like a god, and he waited and waited and waited, pasted against the screaming dirt, dirt of screams, for someone to come and save him that did not exist. And yet Arthur still waited. And Arthur waited and waited, until he could wait no longer. Until he finally turned into the world that those around him had destroyed.

Max Newman is a 20-year-old writer and college student originally hailing from Chicago, Illinois, and currently residing in East Syracuse, NY. From a young age, Max was interested in writing, often scribbling nonsensical stories in makeshift books of stapled printer paper. A writer of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, Newman’s work can be seen in Obie Muse, Oberlin College’s music publication, as well as Cleveland Classical, a publication dedicated to covering classical and jazz music in Northeastern Ohio. In his free time, Newman enjoys listening to and producing music, watching soccer, and spending time with his dog, Gracie.